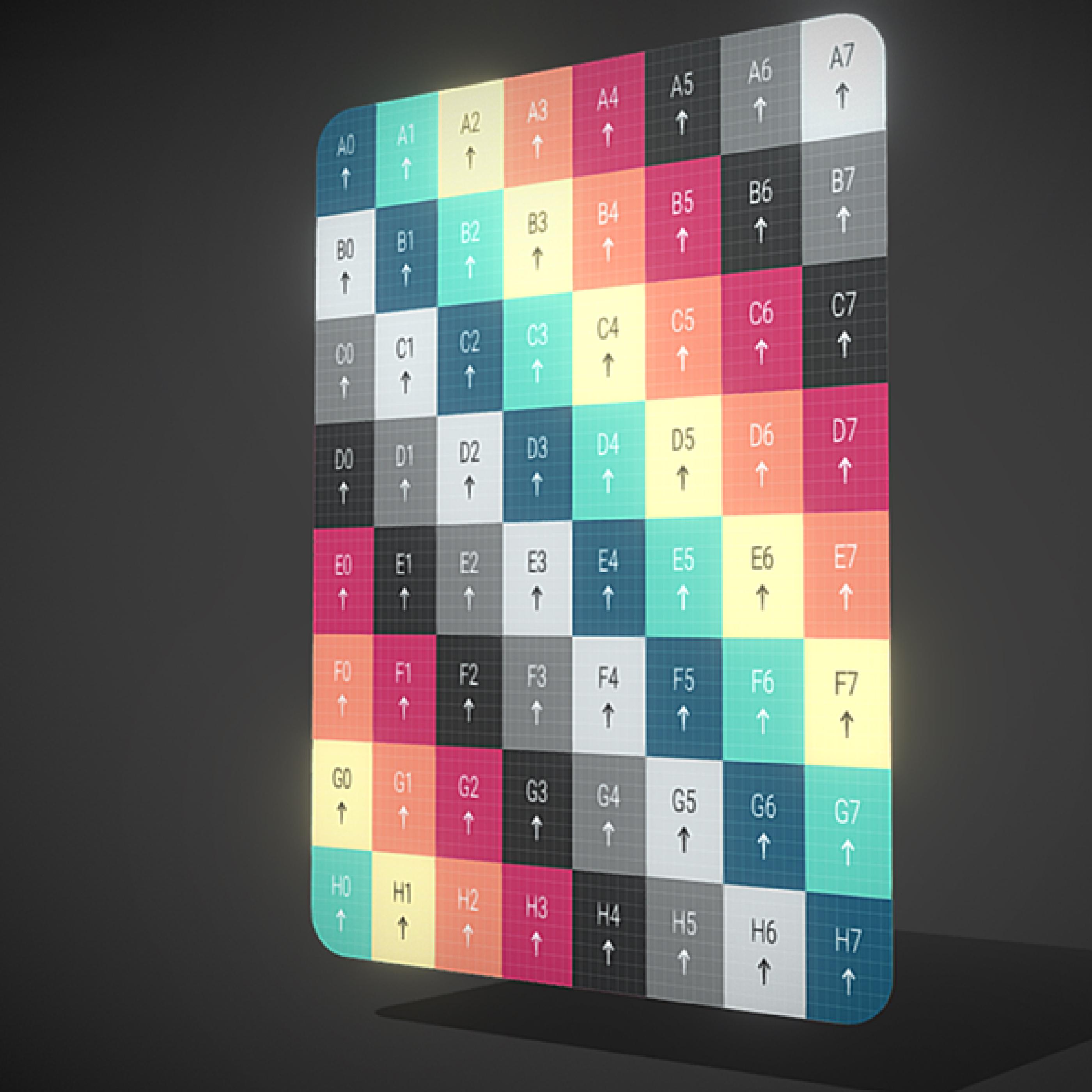

Kairos is a devblog documenting the journey of creating an indie card game set in a zombie apocalypse. Developed using Unity and the custom-built Game:Work framework (MIT license).

Follow along as I share progress on everything from 3D card rendering and physics-based interactions to game design decisions and the challenges of solo development 🤙